Page Content

Meriel Hughes, a teacher from Jasper Place High School in Edmonton, and Benita Greenwood, from Westwood Community High School in Fort McMurray, take part in a group cultural tour from Molde, Norway to a museum on Hjertoya Island during an exchange visit.

—Photo by John Scammell

Multilateral accountabilities build adaptive capacity

Inspired and informed by Sam Sellar’s work in the Australian PETRA project (2014) and committed to the goals of creating a great school for all with our international partners Finland and Norway, the Jasper Place High School community embarked on an enterprise to contribute to current understandings that engagement and equity within learning environments directly affect student outcomes. Dubbed ResponseAbility Lab, this work represents just one initiative over the past few years that has been supported by the international partnerships sponsored by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and the network of schools we have been working with both here in Alberta as well as Finland, Norway and New Zealand.

Inspired and informed by Sam Sellar’s work in the Australian PETRA project (2014) and committed to the goals of creating a great school for all with our international partners Finland and Norway, the Jasper Place High School community embarked on an enterprise to contribute to current understandings that engagement and equity within learning environments directly affect student outcomes. Dubbed ResponseAbility Lab, this work represents just one initiative over the past few years that has been supported by the international partnerships sponsored by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and the network of schools we have been working with both here in Alberta as well as Finland, Norway and New Zealand.

Responseability Lab

First and foremost our international network recognizes that schools that pursue a broad range of goals beyond narrowly defined definitions of learning, referred to as “learnification” (Biesta 2010), experience improved academic results as well as better citizenship, health, resiliency and life-preparedness outcomes. Across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) we increasingly see a preoccupation with rankings on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and other benchmarks that inevitably lead to short-term reactive policies that do not build the capacity to respond to local contexts and often serve to distract schools from the broad goals of a public school education (Alberta Teachers’ Association 2016).

Instead, our Alberta high schools’ network takes up a multilateral accountabilities framework (Murgatroyd and Stiles 2015) that moves beyond simply generating numbers to tracking how our school might engage broader measures of success to enhance the school’s ability to respond to the unique needs of our community. This work is part of an emerging shift to developing adaptive capacity (Sussman 2004). By engaging students in the work of learning and of becoming, this process builds a school’s ability to be a responsive organism that adapts to and works within changing student, community and sociopolitical contexts. ResponseAbility Lab tests the notion that schools can and should evaluate how they nurture students’ abilities to learn, grow, create and thrive in social, academic and professional settings.

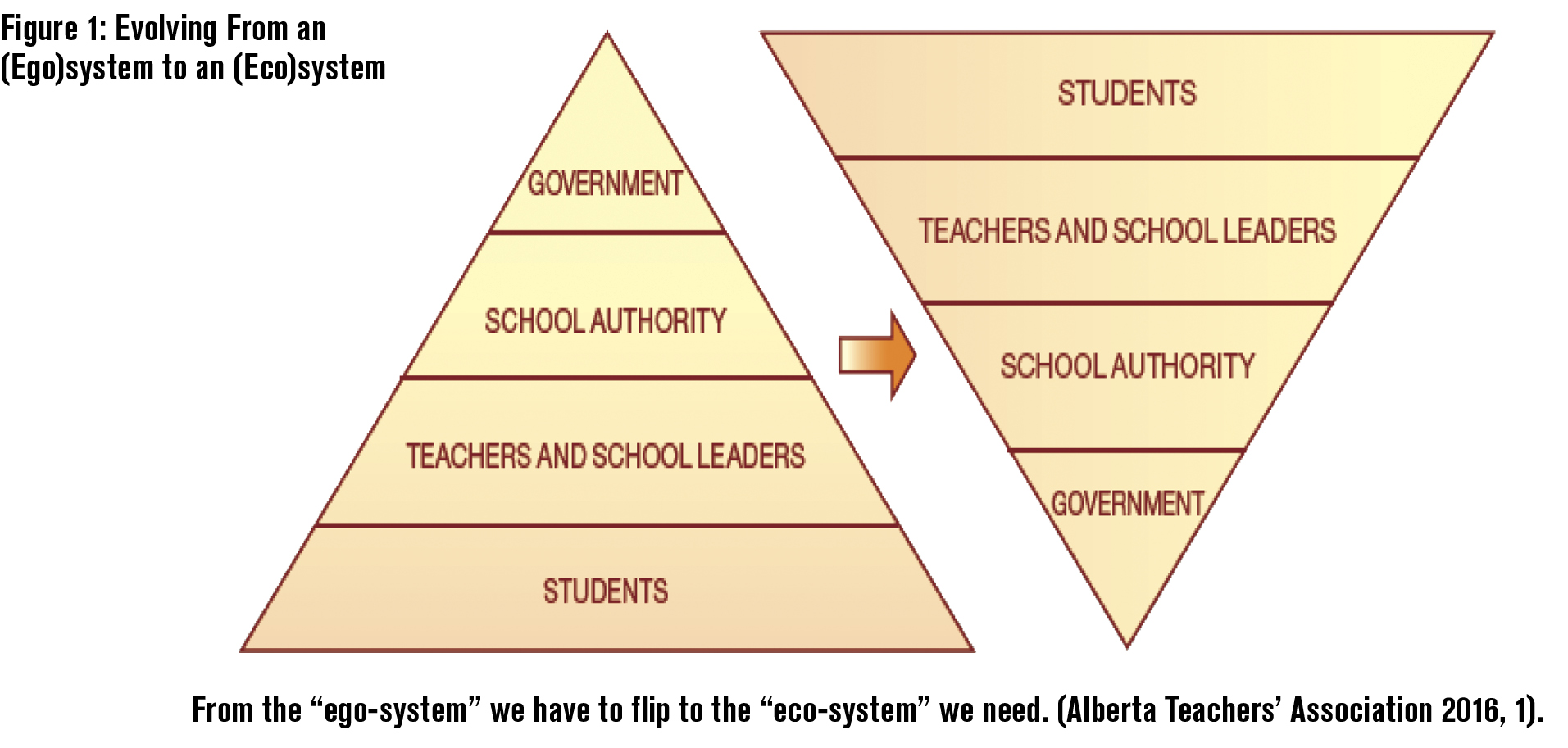

A central element of the conceptual frame for building adaptive capacity is the recognition that the school site is part of a complex organic system of relationships that is nested in the community, education systems and the broader sociopolitical milieu. This paradigm shift calls upon school reformers to figuratively “flip the system” by seeing the classroom and school site as the leverage point or nexus for innovation rather than the system leadership (Evers and Kneyber 2015).

Jasper Place is a diverse learning community with more than 2,400 students and 150 staff from a range of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. Students arrive from approximately 25 feeder schools with various degrees of achievement, confidence and resources with which to approach their high school experience. For these reasons, building adaptive capacity offers an alternative to gathering data for purposes that seem detached from the immediate needs of our students and community.

In February 2015, our school-based ResponseAbility Lab action research team invited 110 teachers and 50 support staff members, six classes of students from grades 10 to 12, a group of alumni students and three groups of community stakeholders to reflect on the school’s programs and environment and develop characteristics and indicators of two pillars: what does an “engaged” school and an “equitable” school look like?

Over the course of two months, through a series of focus groups, we asked ourselves as a school community to explain what equity and engagement meant to us, and then articulate what these values might look, feel and sound like in the school’s context. What emerged was a context-specific list of values around equity and engagement within the school. The project also generated a separate list of indicators that researchers or school staff might use to measure the values and to develop short- and long-term targets for the school. While a full analysis of our work is the focus of a future publication and permutations with our international network, one compelling thread — the multiple definitions of what constitutes success in school — is described in what follows.

Multiple Realities For Defining A Great School For All

Over the course of our work it was clear that there was at times a disconnect between what staff felt about students’ school experiences and what students described as their lived experiences in school. These conversations and protocols highlighted the simultaneous presence of multiple face-to-face and virtual realities (through social media) in our school’s ecosystem. We were challenged to cope with many constructions of reality, as there were diverse perspectives about what was happening in our school.

As a staff, we have talked about and committed ourselves to the principle of equity, but repeatedly the question was raised, “What about the diplomas?” Teachers questioned whether we could really trust the theory of achieving excellence through equity. Diploma exams were an elephant in the room and great discomfort permeated staff discussions. Teachers felt apprehensive that they might not be able to provide reliable evidence to parents that a child had learned without the exit exam to verify student learning. Although many teachers saw differences between student achievement in their classes and achievement on a diploma exam, there was a sense that faith in teacher judgment had been eroded in Alberta’s current context.

Many important questions were raised once we, as an institution, began to dig into the layered assumptions of traditional accountability. If we learned, for example, that students should have longer in school to achieve optimal outcomes of learning, how would our results falter as we continued to measure the number of students who complete high school in three years? How can schools provide reliable evidence of meeting expectations?

Although a sense of vulnerability was present, participants began to explore other ways of addressing curricula or counseling students that might veer away from the norms presented by the current accountability regime. There seemed to be a sense of excitement and a tenor of risk-taking from the fact that we were just going ahead and changing the system rather than waiting for permission. Innovation seems imminent in this state of disequilibrium. The reaction of staff feeling that they might not be meeting the needs of all students seemed to create a sense of urgency to innovate and respond in a new way. In finding the chaotic edge, the dissonance between what we know and what we value, we also found new motivation, energy and hope.

Moving Beyond Boundaries

Crossing boundaries beyond subject departments, schools, jurisdictions, and even forming international networks and communities of practice, is essential to developing improved practices in measuring school success. Thinking ahead, leading across and delivering within remain the leadership strategies we pursue in our international network that were set out in the ATA’s A Great School for All initiative launched in 2011. Across the international network we work in, principals and teachers continue to partner in the community and across school boundaries to foster and facilitate learning networks and communities of practice. “Leading across” was defined as principals, teachers and students crossing school and jurisdictional boundaries to learn from each other. The ability to collaborate, make sense of evidence and learn from one another is necessary, and this dimension builds upon the belief that it is necessary to move outside one’s culture to actually see the culture. It provides a new lens for professionals to question, understand and unpack myths and assumptions that lie hidden in every culture of the school and jurisdiction or milieu within which it is nested.

The process of assessing a school’s adaptive capacity allows discussions to build around a triad of information, values and practices (Sellar 2016) that take us to the focal question driving our work: how can international partnerships ensure that we co-create a great school for all? As one of the teachers observed, “ultimately this question drives us past a narrow focus on accountability to a focus on professional response-ability.” Taken to the jurisdiction and system level, this shift offers important possibilities for rethinking education systems not as ego-systems but ecosystems – in a word, flipping the system.

From Ego- To Eco-System

The commitment to distributed leadership with an ecosystem that authentically includes student agency is illustrated by the experiences of a student who approached the leadership team to request the opportunity to address the school staff about the Jumu’ah, the weekly congregational prayer held by Muslims every Friday. Encouraged by the conversations being held in the school about equity and student engagement, this student felt the imperative to speak about the Jumu’ah club to bring some clarity about the club’s history and purpose. The student was granted the opportunity to address the entire staff at the beginning of a professional learning day at the school. All student presenters commented on the importance of having an opportunity to share with staff and how valued they felt by the responses they received from the presentation. The reaction by staff was overwhelming and a decision was reached to have all school meetings begin with student presentations.

The work of the ResponseAbility Lab acknowledges that current accountability systems and the neoliberal “commodification” of education present both challenges and opportunities (Sahlberg 2014). Just as important, as we in our international network redefine “school,” and challenge the notion of school as simple resource management, we can question what it means to be a citizen and to prepare students for more than narrow academic targets or job skills required in the marketplace. Our work alongside our international partners supports critical research into how schools and policymakers transition from narrow frameworks of accountability into systems with multilateral and multiple accountabilities that allow for greater adaptive capacity within schools and systems.

In our school and indeed as we find with our partners both in Alberta, Norway and New Zealand, accountability measures no longer function exclusively in an external manner to measure schools and student achievements, but instead are the drivers that shape the teaching and learning conditions of practice within the educational system. In many instances, we were unaware of how ingrained the accountability measures are that shape all that we do in schools, like goldfish who are unaware of the water in which they swim (Sellar 2015). To remain adaptive, we must constantly remind ourselves of the water we swim in, the context we inhabit.

The recognition of students, teachers and others as important voices in the conversations demanded a respect for differences and an assurance of the safety of all participants. There is global recognition that the role of school is transforming. All partners, including students, are vital to the conversation. While many reforms aim to graduate more students as literate, numerate, productive citizens (McMahon 2013), it is imperative that we attend to the fuller meaning of democracy and the purpose of education by asking the question more frequently: “education according to whom and for whom?” (p. 17).

This is a question we pursue in our partnerships, in which we are compelled to question what it means to live in a civil society and to respect one another, how to understand one another’s differences and, essentially, how to accept one another.

References

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA). 2016. A Great School for All: Moving Forward Together. Edmonton, Alta: ATA.

Biesta, G. 2010. Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

Evers, J., and R. Kneyber, eds. 2015. Flip the System: Changing Education from the Ground Up. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lingard, B., A. Baroutsis, S. Sellar, M. Brennan, M. Mills, P. Renshaw, R. Waters and L. Zipin. 2014. The PETRA Project—Learning Commission Report: Connecting Schools with Communities. Brisbane, AU: University of Queensland and Victoria University.

McMahon, B. 2013. “Conflicting conceptions of the purposes of schooling in a democracy.” Journal of Thought 48(1), 17.

Murgatroyd, S., and J. Stiles. 2015. “Building Adaptive Capacity in Alberta Schools.” Paper presented at the Building International Partnerships through Adaptive Capacity Institute, Banff, Alberta, November 20–21.

Sahlberg, P. 2014. “Excellence through Equity.” Presentation to the Alberta Teachers’ Association fall planning meeting, Banff, Alberta, September 12.

Sellar, S. 2015. “Rethinking Accountability.” Presentation at Adaptive School Leadership: An International Network Committed to A Great School for All, Banff, Alberta, November 20–22.

———. 2016. “Rethinking Accountabilities.” Presentation to Central Alberta Teachers’ Association Convention, Red Deer, February 19.

Sussman, C. 2004. Building Adaptive Capacity. Boston, MA: Management Consulting Service.

Jean Stiles is the principal of Jasper Place High School in Edmonton and is a member of the Alberta Teachers’ Association’s international partnership working group.